The Santa Anna Glass Plant

Few citizens of Santa Anna know that our city has been pivotal in a suit argued before the Supreme Court.

Yes, THAT Supreme Court.

And few of us know that the preeminent historian of Texas, Walter Prescott Webb, wrote in detail about the case in his book Divided We Stand: The Crisis of a Frontierless Democracy (1937). In the book, Webb issued a strong condemnation of the power of northern corporations over the economic interests of the West and South.

The story begins with the earliest white settlers of this area. These pioneers soon learned that Santa Anna’s Peaks contained deposits of pristine silica sand. It was exposed to the surface in several locations, and settlers immediately recognized the potential for its use in mortar for stones and brick. Lacking a source for man-made cement, they used lime mixed with ash from burnt wood as the cement and the sand brought from the mountain as the aggregate. Anyone who has worked with the older buildings on main street, especially the stone buildings, has encountered this type mortar. It is much softer than cement mortar, and prone to wash out when hit by water, but it has served in many Santa Anna buildings for over a century.

Several chroniclers of our community (such as Ralph Terry) have pointed to 1911 as the year when silica sand began to be mined in earnest and shipped by rail to glass factories across the nation. Extremely high in silica content, perhaps as much as 98% pure, the glass made from Santa Anna sand was well suited for manufacturing high-quality products, especially milk, vinegar, and beer bottles. It was also uniquely suited to shipment by rail since it was easy to load and unload.

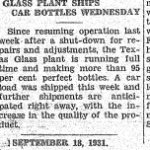

In 1930, businessmen of Santa Anna recognized the potential of the sand for the community, so they created the Texas Glass Company. They situated the plant east of town proper near the railroad, with a siding for loading the finished products. Once in production, the plant operated twenty-four hours a day and produced excellent bottles. Two years later, the owners sought investment capital and secured a loan, but they were unable to repay it.

When banks in Fort Worth and Austin foreclosed on the business, two engineers formerly employed by Three Rivers Glass Company took it, creating the Knape-Coleman Glass Company. Operating at full steam until 1936, Knape and Coleman upgraded the facility by installing a new process using automatic feeders on the production line. This process had been patented, along with over 600 other patents covering virtually the entire process of glass-making technology, by the Hartford-Empire Company of Connecticut.

Though making no products themselves, Hartford-Empire successfully sued several small producers of glass, including Knape-Coleman, for patent infringement. Using the time-honored tools of large corporations, Hartford-Empire’s army of lawyers harassed, tied-up, and otherwise browbeat the small producers of glass bottles who were unable to field their own lawyer army. Knape-Coleman finally settled the suit by obtaining a license to produce milk bottles for six months, agreeing to ship all their production machines to Hartford-Empire at the end of the license period.

True to their word, Knape and Coleman freighted their machines by rail out of Santa Anna when the license expired and continued to produce milk bottles by hand. But they were unable to maintain the effort using hand processes. They sold the plant to Liberty Glass of Liberty, Oklahoma, which soon shut down the facility and razed it. Webb’s Divided We Stand has pictures of the demolition of the plant in 1936.

Two artifacts remain of this once prominent employer of Santa Anna citizens. Vintage milk bottle collectors search for the unique greenish bottles embossed on the bottom with a ‘K’ superimposed over a ‘C’. These rare finds are all that remain of Santa Anna glass production. The other relics are pieces of kiln tiles scattered around the vicinity of the city. Great chunks of greenish glass are embedded on one side of the tiles making these remnants easily identifiable. When the giant power lines came into Santa Anna on the east edge of town, passing just behind the Quonset huts belonging to Santa Anna ISD, many of theses tiles were uncovered and left scattered over the ground, mute testimony to the passing of an era.